Groin hernia and you

- What is a groin hernia

- What causes groin hernia

- What are the symptoms

- How are groin hernias diagnosed

- Does my groin hernia need to be treated?

- What does surgery involve?

- Which operation should I have?

- When will I go home?

- What are the risks of surgery?

- How do I prepare for surgery?

- What happens when I go home?

- What should I watch out for in the first week following surgery?

What is a groin hernia?

A hernia is a defect (hole) in the abdominal muscles through which the abdominal contents (usually fat but sometimes intestines or other abdominal structures) can protrude. These occur at natural points of weakness in the muscles of the abdominal wall, usually in the inguinal (common), or femoral (less common) regions of the groin.

The term inguinal and femoral simply refer to the position in the groin where these hernias occur.

They can occur on one or both sides (bilateral) of the groin.

What causes a groin hernia?

Hernias may be present at birth, or develop in later life as a result of any factor that weakens the tissues of the abdominal wall (e.g. inherited genetics, increasing age, smoking, increased pressure within the abdomen – long term cough, §sustained heavy lifting).

Usually the development of a hernia is a combination of these factors. There is no good evidence that occasional heavy lifting is a risk factor for developing a hernia.

What are the symptoms of a groin hernia?

Remember a hernia is simply a hole in the abdominal wall – a hole through which something can protrude. The hole itself is not painful. There is sometimes, but not always, some discomfort– but it is not excruciating pain. So as a rule of thumb – if when you stand up or cough there is no swelling or a lump to see or feel – it is unlikely that you have a hernia – unlikely but not impossible.

When you lie down the protruding bit usually drops back through the hole and there is often nothing to see or feel – unless the hernia is stuck in the hole in the muscles. If the hernia doesn’t go back when you lie down this is called irreducible, (or sometimes incarcerated). That is why doctors examine you standing and coughing when checking for a hernia.

How are groin hernias diagnosed?

Most groin hernias are diagnosed by the clinical history and examination alone. Occasionally, if the diagnosis is unclear or if pain is the predominant symptom and there is no obvious swelling further investigations may be used. These include MRI scans, herniography and ultrasound scans. However, these scans have the problem that they may ‘over diagnose” hernias. In such cases they report a ‘possible’ or ‘small bulge’, which is really just a bit of normal tissue. So you can’t rely 100% on scans. Be guided by your surgeon.

Does my groin hernia need to be treated?

Although having a hernia is not usually a serious condition, hernias will not go away without surgical repair.

There is always the option to do nothing. This may be appropriate for longstanding hernias, which do not cause any symptoms and in patients with lots of other medical conditions. However, the majority of hernias will gradually become bigger and more uncomfortable with time, no matter how careful you are. Wearing a special device called a truss (support) to stop the lump coming out of the hole was used in the past, but is now thought to have no or limited benefit and are also fairly uncomfortable.

What does surgery involve?

Broadly speaking, there are two ways that a groin hernia can be fixed.

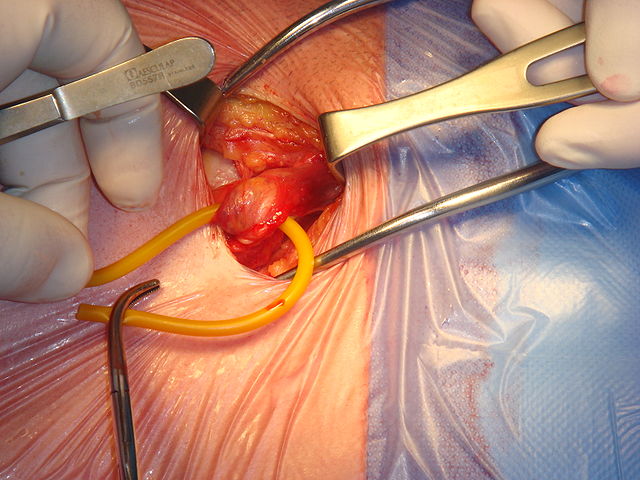

Open surgery

This can be carried out under local or general anaesthetic. Your surgeon will discuss this with you. It’s called ‘open’ because a small incision is made in the skin (usually 2.5 – 3 inch), in the groin area. The open approach can be carried out using either general or local anaesthetic, and this will be dependent on both your current health condition and preference after discussion with your surgeon.

At operation the hernia is identified and the hole is either stitched closed (not at all common now) or (much more commonly) a mesh is placed over the hole and fixed using fine stitches. The mesh acts like a scaffold and your own tissue will grow through the mesh to reinforce the weakened area without putting tension on the surrounding tissues.

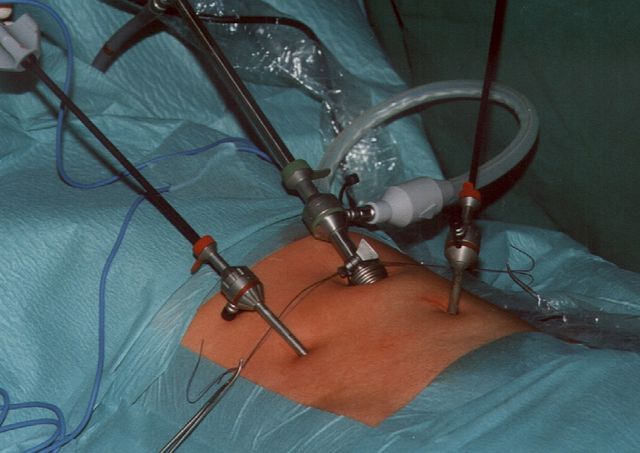

Keyhole or laparoscopic surgery

Your operation will be carried out under general anaesthetic. One small cut (1-2cm long) near the bellybutton and two small cuts are made in the lower abdomen. Carbon dioxide gas is used to inflate your abdomen and a small telescopic camera is then inserted to view the hernia from within the abdomen. This means that the surgeon is looking at the hole from the inside of the abdomen. A mesh is then place over the hole. It is a bit like repairing a puncture in a tyre with a patch from the inside.

There are in fact two laparoscopic methods:

In TAPP (Trans-Abdominal Pre-Peritoneal) the telescope is placed into the abdominal cavity

In TEP (Totally extra-peritoneal) the abdominal cavity is not entered and the operation takes place placed in the space between the muscles and the lining of the abdomen.

There are advantages and disadvantages to both. In expert hands both methods give equally good results, and you should be guided by your surgeon.

All of the operations usually take between 30 minutes and 90 minutes operating time.

Which operation should I have?

Generally speaking there is not very much difference between the operations in practice, as long as they are performed well. The surgeon’s expertise in a particular a technique are at least as important as the type of repair that is being performed, and it is important that this decision is made after discussion with your surgeon.

In certain circumstances keyhole ‘laparoscopic’ repair may be beneficial. These are:

- recurrent hernias (that have come back after being surgically repaired before using the open operation),

- bilateral hernias (hernias in both groins),

- hernias in women (there is some evidence that women have a higher chance of another undiagnosed hernia that is not easily seen during open surgery),

- very active patients whose predominant symptom is pain.

In certain circumstances open repair, using local anaesthetic may be better e.g. patients who are older and have other medical problems, оr patients who do not want a full general anaesthetic.

When will I go home?

With most groin hernia repairs patients are able to go home the same day as their operation. Occasionally people with other medical conditions, or who do not have anyone at home with them need to stay in hospital overnight. Sometime it may be difficult to pass urine immediately after the operation and that is another reason to stay in hospital overnight.

What are the risks of surgery?

Problems after straightforward groin hernia repair are very rare but you do need to know a little about the kind of things that that can occur.

Short-term problems

- Bleeding – can occur after any skin cut

- Infection – can occur after any skin cut

- Seroma – a collection of clear fluid that sometimes occurs after surgery

- Damage to the surrounding structures – the blood supply to the testicle (on the side of the hernia repair) can be damaged (this is very rare in first time hernia repair). Other abdominal structures can be damaged in keyhole surgery (also very rare).

- Haematoma – this is a bruise that can occur in the groin or the scrotum and can be quite dramatic. Whilst a small amount of bruising is normal, a large bruise causing swelling of the scrotum is rare.

- Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism – blood clot in the legs, which may then travel to the lungs can be a problem after any operation. The risk after hernia repair is very low. If you are an ‘at risk’ individual, you will be given special graded compression stockings and possibly blood thinning injections to reduce the risk even further.

Medium and long-term problems

- Recurrence – the hernia comes back – about a 1 in 200 risk

- Long-term discomfort or pain – this is rare but can occur in up to 5% (1 in 20) groin hernia repairs. By long-term pain we mean pain lasting for more than three months after the operation. We don’t know exactly what causes long-term discomfort but one theory is that it is due to inadvertent nerve damage during the operation. The likelihood appears to be higher in patients who have small hernias and whose predominant symptom before the operation is pain.

- Mesh infection – this is very very rare (about 1 in 500 risk). The mesh can become infected – usually from bacteria on the patient’s skin. If this does occur the mesh will normally have to be removed with another operation and the hernia may come back (recur).

How do I prepare for surgery?

The majority of hospitals will now ask you attend a pre-operative assessment clinic or have a telephone assessment. This allows us to assess your fitness for surgery and ensures you are fully prepared for your operation this will include;

- Giving a health history

- Providing blood samples.

- Obtaining an MRSA (Methicillin resistant Staph-Aureus) swabs if necessary.

- Giving a medication history (please bring your medications with you)

- Giving you the opportunity to answer any questions you may have.

What happens when I go home?

- Pain: Over the counter medication i.e. paracetamol/ibuprofen should give adequate pain relief so ensure you have a supply at home. Many surgeons advise that they are taken regularly (i.e. 4-6 hourly as per the instructions) for the first 48hrs following surgery, then continued as required.

- There may be some bruising at the operation site. This is entirely normal and will gradually go down. (If bruising/swelling increases rapidly within hours of surgery and is associated with dizziness/light headedness inform your GP).

- You may notice that there is a numb area below the wound. In most cases these sensations will gradually return, but sometimes a small area of numbness remains.

- Diet: You may eat and drink normally.

- Mobility: This is very important. Try to remain physically active. If you feel tired you should sit down and put your feet up for short periods and not go to bed during the day. This will improve circulation in your legs and reduce the risk of deep vein thrombosis – DVT.

- Hygiene: Shower rather than bath for the first 10 days – the dressing provided should be waterproof but check with your local hospital.

- Wounds: Methods of wound closure vary depending on your surgeon. Sutures are normally dissolvable and you should be able to remove any steri-strips (“butterfly stitches”) yourself at 7 days. Do not change the dressings unless they have become very blood stained, in which case you should also let your GP or surgical team know. Wounds should appear clean, dry and healing. If you are in doubt seek advice from your GPs practice nurse.

- As you recover you will be able to increase your activities. You will be able to return to work within one to two weeks but if your job involves heavy lifting it may be up to six weeks before you can return to work. You should discuss this with your consultant.

- You may drive as soon as you are able to drive safely without impairment to your reaction time or ability to think clearly (normally 48hrs). It is always a good idea to check with your insurance provider.

What should I watch out for in the first week following surgery?

- Severe abdominal groin or testicle pain

- Loss of appetite, increasing nausea or vomiting

- Fever or flu like symptoms

- Redness/swelling at the surgical site

- Calf pain or increasing breathlessness

If you experience any of the above it is important that you contact your GP as soon as possible and it is important, if you have had keyhole surgery, to make them aware of this. (Some hospitals may provide you with a contact number if you experience problems in the first week and it would be advisable to ask if they provide one).